I won’t make a grand commitment to writing every day, or even weekly. I’m stubborn in my ambivalence, although with wobbly legs.

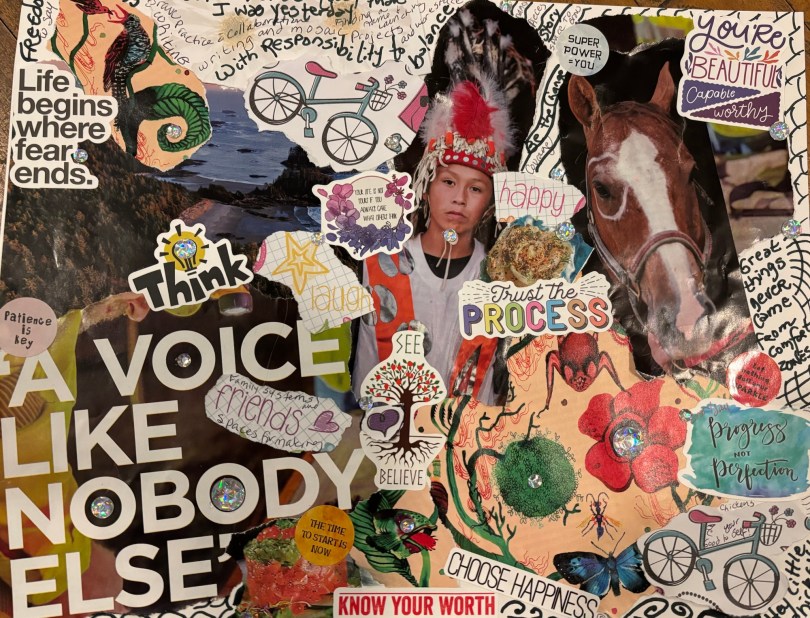

I am trying to “manifest” a life designed by me for my one, true beautiful me. If you had asked my emerging adult self what I wanted out of my life, I would have been want for a clear vision. I think the speed of time as I age has hastened a better grip on wanting to sort this out more clearly. I envision my current life and life ahead, having better balance and less grind; Speaking up over quiet omission; taking what I need over asking permission.

When we moved to Minnesota in 1991, my betrothed began graduate school almost immediately after our wedding, and we settled in to our one bedroom apartment at the Palisades. I don’t recall how we found the Palisades apartment complex—we didn’t have google or the internet yet. We learned about the complex before we moved there, and we arranged for an apartment, sight unseen. Somehow we figured out how to send away for information and received a pocket folder with an application and pages that described the layouts of each unit. Our apartment was on the 3rd floor, in one of the eight buildings (I made that up,) of the complex.

Ours was 800 square feet with an entry that went to the left into a petite galley kitchen, or straight ahead to enter a pie-shaped living room, with an adjacent small bedroom and bathroom. The “dining room,” an extension of the galley kitchen, opened also to the living room, where a balcony and sliding door filled the far wall. We had a mauve futon and a papasan chair from my college apartment, along with an antique Queen sized bed and matching dresser that my parents allowed us to take with us. I recall the spoiled privilege of just assuming I could take “my” bed and dresser, as I had used them throughout my childhood–they were “mine.” I recall my mom’s reaction to my less request than proclamation–a mix of disdain, surprise and ultimately unselfish acquiescence to my assumption. In the category of what goes around comes around, our oldest had a similar conversation with me, when he loaded his Yukon with the lower part of the bunk beds and dresser we bought for his childhood room.

My journey to find employment was less defined than my partner’s decisive plans, (to this day, something I have long been attracted to–his unswerving sense of goal direction.) At age 22, we had just finished college, and I had sought little guidance about finding employment, or even narrowing my ideas about what employment might look like for me with a really broad, liberal arts degree and only limited employment experiences working as teller, flower shop assistant and a line cook. I had an entitled notion that I could send resumes to area fortune 500 companies in the Twin Cities and I would be barraged with calls for interviews.

When after a month of no calls or responses to my carefully printed cover letters and resumes on marble vellum stock, he gently suggested I should find some way to earn a living, as his $8,000 annual graduate stipend was going to have limitations for our shared living. So I went to the want ads in the back of the newspaper and found a teller job at the Burlington Northern Railroad Credit Union, downtown St. Paul. I don’t recall much about the job, except it was a rather small, dark office space, located inside a building, accessible from the internal habitrail-hamster tubes, that connected many of the buildings throughout the Twin Cities. You could enter a random building, take an escalator to the 2nd floor and enter an elaborate system of heated tubes in order to avoid the extreme winter weather conditions common between November and April in Minnesota.

I didn’t last more than four months at the BN Credit Union. Our manager there was an uptight, 30-something lanky white guy, who only spoke to us if we made mistakes. He was too uncomfortable to be anything but direct, which really poked at my inner perfectionist and I felt perpetually doomed to make mistakes. It didn’t take long to feel frustrated by boredom, insecure about the stink-eye glances from our manager when I arrived late, and a complete lack of vision for where this would take me in life. So, when an ad appeared for “Activities Assistant, in the want ads, “experience with music and art encouraged,” I promptly called the number and scheduled an interview.

I have always thought about St. Anthony Park Home as my first “real” workplace. Owned by John, a really kind man, who began his career in that Nursing Home as the Custodian, it was what would now be thought of as a boutique nursing home, a unicorn that remained free of corporations bent on revenue streams dependent on frail humans in need of care and support.

The first person I met, I’ll call him Fred, shuffled over to me with mammoth, scuffed up Bass lace-ups to propel his wheelchair near the front door. His white hair, in need of trimming, fluffed in whisps along his long forehead, and he reached out with giant, silken hands. He asked me if I’d “Get out of here,” with him and a nurse intervened, guiding me to a table in the dining room. Fred waved a wistful and tearful farewell, as if I were his long, lost love, while Dolores, a Franciscan nun, and the designated Social Work Director, walked over from her nearby office and asked what brought me in. She would be my first Social Work mentor and guide.

I interviewed with Susan, summoned by Dolores, who proclaimed with the confidence and fierce smile of a tribal healer, “Hire this woman!” This would begin a truly unique era of friendship and learning about myself as a young adult. I had long thought of myself as a tomboy, and while I had girlfriends throughout elementary, secondary education, and college, I hadn’t fully shared much about my authentic self with other girls or women until this experience. Bonnie, our Director of Nursing, would also share a role of mentor for me. Dolores, previously a school administrator, would become the administrator of a care facility for Franciscan nuns. Dolores hired Bonnie as the Director of Nursing there and together they managed the psychosocial medical care needs of women who had dedicated their lives to serving the Catholic church—until that is, they left together, to work for John at St. Anthony Park Home.

Bonnie and Dolores frequently invited a small group of us, Susan, Lisa, Shirlee and Lynn, to Bonnie’s two-flat St. Paul apartment, for dinner. They shared stories about their work together over the years, Bonnie’s Leukemia diagnosis and her tireless commitment to work, in spite of her health. Dolores told us she had found Bonnie at the nurse’s station, more than once in the midst of her own experimental chemo treatments, still determined to organize charts, policies and procedures.

They told us about vacations they had taken together, a trip to Maine where Bonnie—who had never been to Maine in her life—suddenly told Dolores, “Never mind about the map, I know where we are,” and she proceeded to navigate them to Kennebunkport and the inn where they would stay. She said she would later experience a past-life regression and learned that she had lived there during the time of Protestant persecution of women as witches. She refused to share more about what she learned, as she said she believed her bad health today was likely some kind of karmic penance for the things she had done in that past life.

Bonnie also described her curiosity about Astral Projection, and how when practicing late one night, she was able to project her face through a glass paperweight on Dolores’ bedside table. We listened, slack-jawed with disbelief until she cajoled Dolores to corroborate her story. Do made the sign of the cross and said the experience scared the “living tar out of her,” and she made Bonnie promise she would never do it again. To this day I think Dolores was crossing her fingers behind her back, but I’m desperate to believe truth in the story. Bonnie told us stories about her life, her sister Shelley, who had been brain-washed by and later extricated from a religious cult sometime in the 80’s, She would also tell Lisa and me about and the birth of her first and only child, Erin, who had died shortly following birth, due to encephalitis. I felt like a fool for asking her why she had never married or had children, but she answered unapologetically and without hesitation with her story. We were gobsmacked by the rich experiences of these women, 65 and 45 years old, respectively.

Bonnie and Dolores mentored each of us, encouraging us to recognize our strengths. Bonnie was a pianist and would accompany me on the flute for sing-alongs for our residents. Dolores encouraged me to shadow her when assessing new residents or when offering them emotional support for the many losses and transitions they were managing. Dolores would be the first of several mentors who guided me to go back to school for a Masters in Social Work years later. Bonnie also created a distinct para-professional role called Rehabilitation Assistant for Lisa, who started there as a CNA, but who demonstrated smarts, and a commitment to quality car. Lisa was organized and capable of managing a caseload of those who no longer qualified for Medicare-covered therapies, but who benefitted from continued support for maintenance health. Bonnie and Dolores had relationships with all of the staff, bonding and encouraging everyone to value the care we provided to our residents, but also supporting our individual lives, hopes and dreams.

One day, as I walked past her office, Bonnie invited me in and swiftly gestured to close the door. “You’re depressed, Beth. Do you know what that is?” Shocked and caught off guard, I received her words with the blunt edge of truth to denial. My previous exposure to language about mental health, had consisted of references to “Nervous Breakdowns,” and the idea that someone was “crazy,” if they had any open indications of mental illness. “You’re pale and your usual effervescence has lost its sparkle. Talk to me.” She normalized depression by saying this was an experience she had been through on her own health journey, along with the experiences of loss. She said with a read-my-lips-clarity, there wasn’t a person in our workplace who hadn’t understood depression in some way personally.

She shared her concern for me and offered her help, if I wanted it. There was a mix of surprise and some resentment for me, about being outed for something I still thought more of with stigma than understanding. I felt the relief of being seen, to have words placed across a gap of something I had felt both too proud and ashamed to identify for myself. I was admittedly miserable, having trouble rising in the morning, an over-active appetite, feelings of worthlessness, even thoughts of death–all symptoms of depression. With her encouragement, I would see a therapist for the first time at age 23 and I even tried a first anti-depressant–the start of a long journey toward finding a better sense of my self, a self independent of my family of origin, with some better understood personal beliefs, values and goals.

I am so grateful for the mentors I have met on this, my heroine’s journey. Not that mine is so special or unique, but a tribute to the way mentors can guide us back to helping us define a self. It isn’t so much the advice, but their raw sharing of flaws, kindness, their pasts, their generous presence that allows one to be seen and therefore also see what is witnessed by someone who views you as precious. The witness of inherent beauty of each one self–the self that no longer depends on assurance, agreement, approval or attention from others, but who stands in gorgeous defiance of fear and steps forward. I enjoy when a new mentor emerges and sends that neutral shrug, “you’ll either do it, or you won’t. That’s up to you.”

Bonnie’s life ended just before my baby’s first birthday thirty one years ago. She included each of us in her funeral planning—Lisa, Susan and Dolores gave readings and I played my flute, at her request, to the hymn, “In the the garden.” We were each named a flower in her garden of life, Susan a freesia, Lisa a daisy, Lynn a Lily, Bonnie herself was the Bird of Paradise, Dolores a Rose and I was a Carnation, spicy and multi-colorful in Bonnie’s naming. A bouquet of these flowers sat alongside her photograph at her memorial celebration.

I still have Bonnie’s notes to me, little card and affirmations given along the way, bursts of encouragement, an elixir that still calls, “keep moving, you’ll find your way.” Years later, a life of school, raising children, supporting a driven and ambitious partner, have I slowly begun to recognize that I can steer my own path and step forward for myself. I’m still me, not a bad thing.

I heard this song for the first time about 15 years ago and the lyrics registered immediately–I felt so heard, so understood and knew I wasn’t the only person to feel like I did. How could someone with so many talents, with so much going for her and with so many privileges feel so empty? There was no answer in the song, but validation, oh yes.

I heard this song for the first time about 15 years ago and the lyrics registered immediately–I felt so heard, so understood and knew I wasn’t the only person to feel like I did. How could someone with so many talents, with so much going for her and with so many privileges feel so empty? There was no answer in the song, but validation, oh yes.